Watershed

Watershed and Flash Flood Risk[edit]

A watershed is an area of land where all precipitation collects and drains toward a single outlet, such as a stream, wash, or river. Watersheds come in many sizes—from the small basin that feeds a single canyon to the massive region that drains into the Colorado River. When canyoneering, understanding the specific watershed that affects your canyon route is crucial to evaluating flash flood risk. A storm miles away can still impact your location if it falls within the watershed above you.

Understanding Watershed Boundaries[edit]

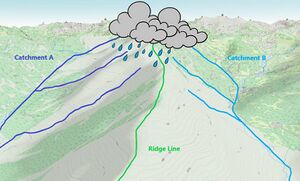

Watersheds are defined by topographic divides—typically ridgelines or elevated terrain that separate one drainage area from another. These divides determine which direction precipitation flows after hitting the ground. Think of a mountaintop: water falling on one side might end up in one canyon, while water on the other side drains elsewhere. The highest surrounding points that funnel precipitation into a single outflow form the boundary of that watershed. Topographic maps are one of the best tools for identifying watershed boundaries. Features such as shaded relief, contour lines, and ridge networks can help you visualize how water flows across terrain.

Relative Watershed Size[edit]

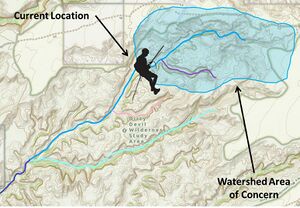

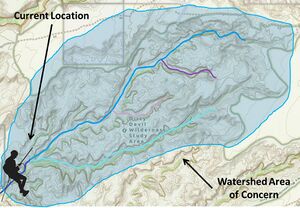

An important point in understanding watersheds is the concept of relative size. Your position within a drainage directly affects what areas are considered part of the watershed and what areas are not. To put this another way, the relative size of a watershed changes depending on where within the drainage you are currently standing.

A general rule of thumb: the higher up you are in a drainage, the smaller the catchment area will be. There are fewer tributaries, fewer side drainages, and less land funneling water into that section. But the further down you go, the more branches feed into the main channel, and the more terrain contributes runoff. So the lower you are, the larger the catchment area becomes.

As a canyoneer, you’re often moving through a portion of a drainage rather than starting at its head and following it to its final outlet. You may begin in one fork, descend through a series of narrows, and exit before the full system ends. But for the purposes of assessing flood risk, what matters is not just the section you’re traveling through—it’s everything upstream of the lowest point you’ll reach in that drainage before exiting it. Any terrain that can funnel water to that point is part of your watershed of concern, no matter where you entered or how far down the system continues after you exit. Anything below that point doesn't pose a flood threat to you, but everything above it does.

This is also why it’s especially important to trace the watershed upstream from your location—not just to the highest visible point, but to all contributing side drainages, benches, and ridges. Knowing how much land can funnel water to where you’ll be is essential for evaluating canyon conditions responsibly.

Watershed Size and Flood Dynamics[edit]

Larger watersheds generally present greater flash flood risk because they have a larger capacity for capturing and channeling precipitation. However, it is the interplay between watershed size and precipitation intensity that truly determines flood potential. A flash flood can occur in large watersheds with low precipitation spread over a wide area, as the small amount of rain accumulates lower downstream. Conversely, smaller watersheds–or even a small section of a large watershed–can experience intense localized flooding if high volumes of rain fall in a concentrated area. Understanding this variability reinforces the importance of reading terrain carefully and knowing which upstream zones contribute to your immediate location.

How to Evaluate Watershed Size and Shape[edit]

Evaluating the size and shape of a watershed is a critical skill for understanding flash flood risk, and it starts with learning how to read terrain. The goal is to map the full extent of the drainage area—that is, to trace the high points that separate your canyon’s watershed from the surrounding ones. These boundaries, often referred to as divides or ridgelines, define where water flows after hitting the ground. When rain falls on one side of a divide, it flows into one watershed; on the other side, it flows elsewhere.

In the context of canyoneering, we’re specifically trying to identify the watershed that affects our route. That includes not only the immediate drainage we’ll be traveling through, but any connected terrain upstream that would funnel water toward the canyon. The relevant watershed is the total catchment area that could deliver runoff to our location—whether directly above or feeding in through side drainages.

The most accessible way to begin this evaluation is by using a topographic map, shaded relief image, satellite imagery, or any map that reveals the land’s form. For someone new to this, the process can start with simply tracing the boundaries visually—using your eyes or finger to follow the outer edges of the drainage and imagine how water would flow toward the canyon floor. The key is to develop an understanding of how elevation shapes the direction of water movement.

Shaded relief, 3D visualizations, and LIDAR-based tools can be especially helpful for highlighting slope directions and subtle divides. In some areas, watershed boundaries are obvious. In others—such as wide, sloping terrain or complex forks—it may take more experience to recognize how watersheds connect and divide.

A highly effective technique is to use a mapping platform that allows you to draw and measure areas. This can be done on paper or digitally using tools like Gaia GPS, CalTopo, or OnX. Even Google Maps has this ability if you create a custom map and use the polygon tool. With any of these systems, by dropping points around the visible ridgelines, you can draw a polygon that outlines the entire watershed. These tools will usually calculate the enclosed area automatically, giving you a rough but useful estimate of the drainage size in square miles, acres, or square kilometers.

This process is about more than just measurement. Drawing the watershed boundary yourself forces you to think through which slopes and tributaries contribute to your canyon and which ones don’t. You’re not just trying to calculate area—you’re trying to understand where water could come from. The goal is to trace the full boundary of the drainage that feeds your canyon and identify any connected terrain that could funnel water into your route. This habit strengthens your ability to read terrain, recognize upstream risk, and focus your attention on what actually matters when evaluating weather and flood potential.

What Canyoneers Should Do[edit]

- Learn to read topographic maps and imagery to identify watershed boundaries on maps using ridgelines and topographic divides.

- Use digital tools to draw and measure the watershed area to get a rough estimate of size.

- Identify upstream features like benches, bowls, or side drainages that could deliver runoff to your location.

- Visualize how water will move through the drainage system—where it will converge, accelerate, or temporarily pool.

- Determine where to monitor forecasts and radar based on what land drains into your canyon.

Understanding a watershed means understanding what terrain can affect your safety. It tells you not just where rain might fall—but what will happen when it does, and where that water will go next.

Notes on Watershed Data and Canyon Ratings[edit]

Some additional tools and watershed data may appear in canyon beta or mapping databases. These often include metrics such as:

- Drainage Area – the total surface area that contributes water to a canyon route. Larger drainage areas generally indicate greater flash flood risk.

- Stream Order – a classification indicating how many tributaries have joined. Higher order streams suggest more cumulative input.

- Average Flow – modeled from long-term precipitation and snowmelt data. This can indicate whether a canyon is normally dry or has perennial/seasonal flow.

- Stream Level – how far a given stream is from the final outlet (e.g., ocean or major river). Higher levels may suggest lower regional flow impact.

In dry regions like Utah, even canyons with small drainage areas can be hazardous due to slickrock terrain and rapid runoff potential. In contrast, canyons in places like Oregon may feature spongy, forested ground that absorbs water and releases it slowly.

Understanding the watershed is more than a background concept—it’s a map of risk. When rain falls, it moves downhill. Knowing where it will go, and how fast, can make the difference between a safe passage and a dangerous one.